The Mississippi River level measured at Memphis, Tennessee, has dropped to severe low levels for the third year in a row. As of 11:35 a.m. on Sept. 23, 2024, the river level fell to -10 feet.

In the past 10 years, the Mississippi River has fallen below the established zero level[1] during harvest (i.e., Aug. 1 through Nov. 30) seven times. However, the level has only fallen to the “low” stage – defined by the National Weather Service as -5 feet – four times (2015, 2017, 2022, and 2023).

The river level has serious implications for cash basis, or the local cash price offered by a grain elevator less the futures price traded on a global market.

Barge Freight Rates

Barge freight rates are established by the U.S. Inland Waterway System using a percent of tariff system. Benchmark rates are based on the tariff rates from the Bulk Grain and Grain Products Freight Tariff No. 7, entered in 1976 between the U.S. Department of Justice and Interstate Commerce Commission (USDA-AMS, 2024).

While these rates are no longer directly applicable, they are still used to calculate the percent of tariff. Calculating the percent of tariff consists of dividing today’s tariff rate by the 1976 tariff rate. The three-year average percent of tariff rates indicates the weekly barge freight rate tends to be near 360 percent of tariffs, or about $11.23/ton[2] (USDA-AMS, 2024).

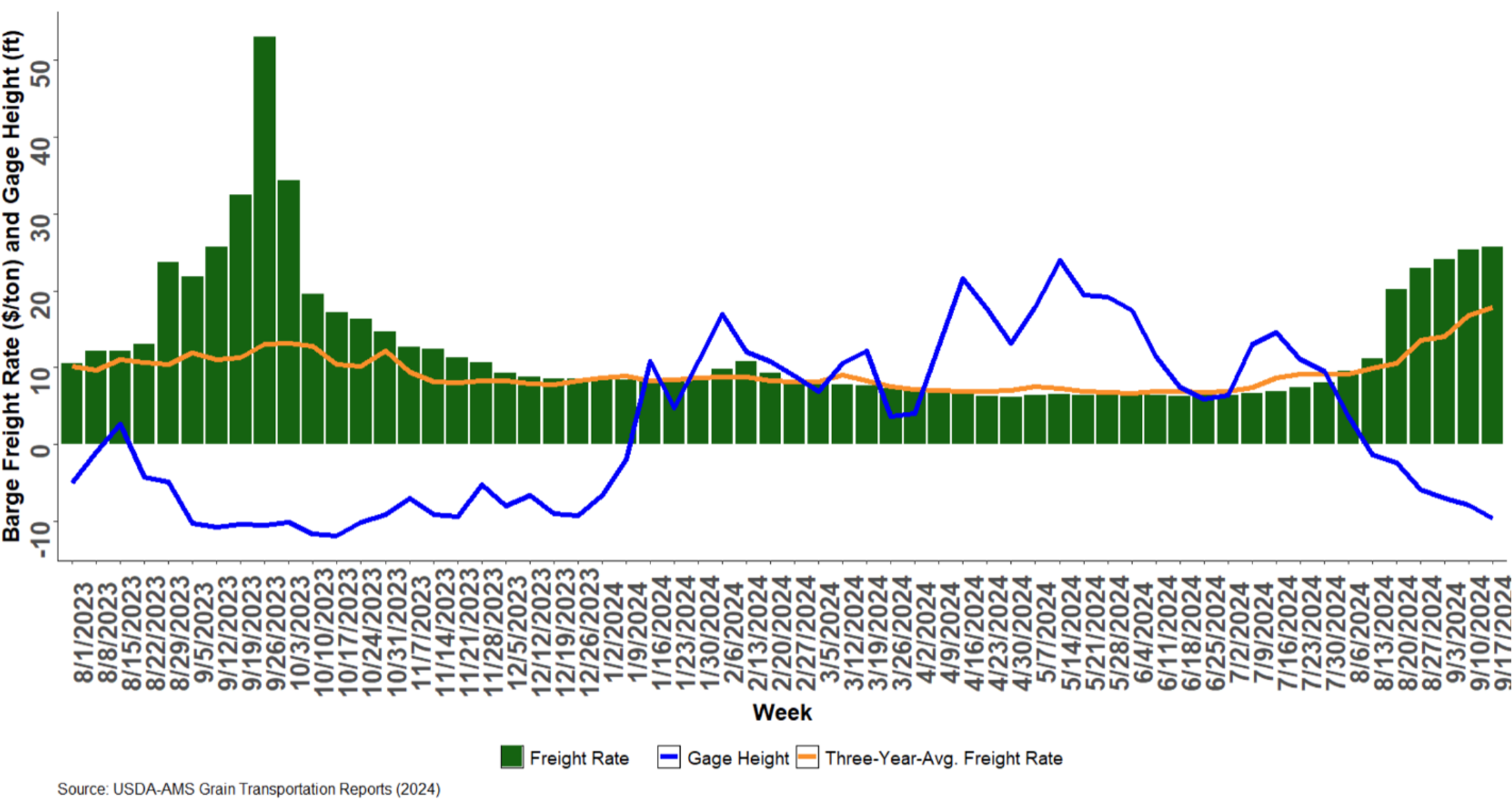

Figure 1. The relationship between the Mississippi River level and barge freight rates for moving cargo from Cairo, Illinois or Memphis, Tennessee.

Low Mississippi River levels have a negative effect on corn and soybean basis through the barge freight rate (Figure 1). For example, the week of Sept. 26, 2023, the barge freight rate was 1,689 percent of tariff, or $53.03/ton, which means the cost to transport grain from Cairo, Illinois, or Memphis, Tennessee, to the port of New Orleans was four times higher than the three-year average for the same week.

Figure 1 plots the Mississippi River level measured at Memphis, Tennessee, for the period Aug. 1, 2023, through Sept. 3, 2024. This figure also provides the weekly average freight, as well as the expected barge freight rate measured by the non-drought three-year average freight rate (i.e., 2019-2021). As the gage height falls, barge freight rates increase, and vice versa.

The relationship between the futures price and the price at local cash markets can change abruptly due to economic or environmental events, such as low river levels.

Local cash bids offered by elevators on the Mississippi River tend to be influenced by river level in periods of drought, because it is more expensive to ship the same amount of grain in more loads due to reduced barge draft (Biram, et al., 2022; Biram, 2023; Gardner, Biram, and Mitchell, 2023).

Figure 2. Daily Soybean Basis at Helena, AR in Harvest Window.

Figure 2 shows the soybean basis response to low river levels in Helena, Arkansas, in 2022 and 2023 with another downward trajectory for 2024 as of Sept. 20, 2024.

Figure 2 shows the historical daily basis for soybeans during the months of July through November. The blue, orange, purple, and green lines denote the 2021, 2022, 2023, and 2024 crop years, respectively. The solid red line denotes the non-drought five-year average basis for a grain elevator in Helena, Arkansas.

The non-drought five-year-average provides the “normal,” or “expected,” basis. The dashed vertical line denotes the basis most recently reported (-26) on Sept. 10, 2024, which is five cents below the five-year-average basis of -31 cents.

While it may appear that the current basis in the heart of the Mid-South Delta region is similar to the non-drought five-year-average, this should be interpreted with caution.

Upon closer inspection, the 2022 crop year also saw relatively strong basis at this time, but a steep decline followed. The relatively strong basis in the first week of September is likely due to only 30% of the midsouth soybean crop being harvested with the remaining occurring by mid-November, along with recent rains, including those from Hurricane Francine.

A potential option farmers might have is to store grain in the bin and market grain in the post-harvest window as described at length in previous Southern Ag Today articles (Gardner, 2023; Gardner and Maples, 2023; Gardner, 2024).

Historically, futures and basis tend to recover in the months when there is little domestic production to buy and stocks are drawn down. We note that the USDA Marketing Assistance Loan (MAL) program may be an additional tool to add to a post-harvest marketing strategy.

A benefit to using MALs is the offered interest rates are below the market average saving potential interest expense. Since grain sitting in the bin is not paying off the operating loan taken at the beginning of the crop year, interest accrues on the operating loan, creating the opportunity cost of storage in addition to the explicit costs of handling and drying (Gardner, 2023; Smith, 2024).

[1] According to the National Weather Service, silt may deposit in a river channel filling it up, or the channel may be washed deeper due to strong currents. Establishing a gauge zero level maintains consistency in river level measurements over time (National Weather Service, 2024).

[2] This figure is found by multiplying the percent of tariff, which in this example is 3.60, by the benchmark rate for the Cairo-Memphis ports which is $3.14.

This information is provided by Southern Ag Today.

The post Low River Levels on the Mississippi River: Not the Three-peat We Want appeared first on Soybean South.

[#item_full_content]